In a Nutshell: What You Need to Know About the FCPA in 2015

I. Introduction

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) continued to be a top enforcement priority for the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 2015, with agencies bringing enforcement actions against eleven companies and imposing total monetary sanctions of more than $184 million. Although these figures may appear somewhat muted compared to those of past years, recent policy guidelines, staff changes, and administrative procedural changes all suggest that the DOJ and SEC are gearing up for what promises to be a busy 2016 and beyond. Indeed, just days ago, the DOJ and SEC announced that VimpelCom, the world’s sixth largest telecommunications company, and its Uzbek subsidiary have agreed to pay $397.5 million to U.S. regulators and $397.5 million to Dutch regulators to resolve charges stemming from over $114 million in bribes funneled to an Uzbek official. Related enforcement actions of similar magnitude against two other telecommunications companies are expected to follow.

2015 provided ample evidence that U.S. regulators will continue to advance an expansive interpretation of the FCPA. For example, Hitachi settled FCPA claims based on allegations that it “knew or could have learned” that a company was acting as a front for a foreign political party. The “could have learned” formulation appears to constitute a lower hurdle than the DOJ and SEC’s traditional “knew or should have known” standard, heightening the already substantial risk associated with doing business with third parties abroad.

Among the policy changes announced in 2015, DOJ promised increased transparency regarding charging decisions in corporate investigations and prosecutions. An immediate tangible example of this policy was DOJ’s announcement that it would not prosecute PetroTiger Ltd., owing in part to the company’s “voluntary disclosure, cooperation, and remediation.” This marks only the second time that DOJ has publicly announced an FCPA-related declination. In this case and numerous others throughout the year, both the DOJ and SEC repeatedly stressed the importance of voluntary disclosure and cooperation with FCPA investigations.

Eleven individuals were charged with FCPA violations in 2015, and DOJ signaled in a new policy memorandum that it intends to devote increasingly more of its resources to prosecuting individuals. Individual prosecutions have historically been challenging for the agencies, since many of the individuals involved (as well as many of the witnesses and relevant documents) are often located outside the United States. DOJ also encountered some judicial pushback in 2015 when a court held that non-resident foreign nationals cannot be subject to criminal liability under the FCPA based on traditional theories of accomplice liability. Nevertheless, DOJ has demonstrated that the FCPA is only one of many tools for fighting corruption. The ongoing FIFA case, for example, involves allegations of wire fraud, money laundering, and racketeering (as FIFA does not qualify as a “foreign official” under the FCPA). DOJ has also used the Money Laundering Control Act as an anti-bribery tool to prosecute foreign officials who are not subject to the FCPA.

In a preview of what to expect in 2016, DOJ warned last quarter that it is “currently focusing on bigger, higher-impact cases, including those against culpable individuals.” To that end, DOJ added 10 new staff members to its FCPA unit, hired a compliance expert, and tripled the number of FBI agents dedicated to investigating foreign corruption. Thus, although overall enforcement was somewhat down in 2015 in terms of the total number of enforcement actions and the size of the corresponding monetary penalties, we expect to see more (or at least larger and more novel) FCPA cases in the coming year.

In short, while comparing the number of enforcement actions or the total penalties paid in a particular calendar year can yield useful metrics, the particular ebb and flow should not conceal the more fundamental point: FCPA enforcement remains a high priority for U.S. officials and promises to remains so in the foreseeable future.

II. What the DOJ/SEC Said About FCPA in 2015

As was the case in 2014, last year the FCPA was a hot topic for DOJ and SEC officials. Common themes included the following:

FCPA Remains a Priority

In 2015, Loretta Lynch became the first U.S. Attorney General to have significant FCPA experience. She previously served as the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, during which her office conducted a number of FCPA investigations. In her confirmation hearings, Attorney General Lynch confirmed that she will “continue to ensure that fighting corruption overseas, as well as domestically, remains a top priority for the Department.”

Ms. Lynch also rejected calls for substantial reforms to the FCPA. In particular, Ms. Lynch addressed proposed reforms by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which included limiting a company’s liability for the actions of a subsidiary, adding a “willfulness” element for corporate criminal liability, and changing the definition of a “foreign official.” Ms. Lynch stated that changes proposed by the Chamber “[1] would be a significant departure from the general principles of corporate criminal law…[2] are contrary to Congress’s intent in enacting the FCPA and [3] would impose often insurmountable obstacles to effective enforcement of the FCPA.”

Individual Accountability for Corporate Misconduct—The Yates Memo

In September, Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates issued a new policy memorandum addressing individual accountability for corporate wrongdoing. Known as the Yates Memo, this policy memorandum outlined the following six “key steps” that DOJ attorneys must follow when investigating corporate misconduct:

- To qualify for cooperation credit, corporations must provide DOJ with all relevant facts relating to the individuals responsible for the misconduct;

- Criminal and civil corporate investigations conducted by DOJ should focus on those individuals responsible for the misconduct;

- DOJ civil and criminal attorneys handling corporate investigations should be in routine communication with one another;

- Absent extraordinary circumstances, DOJ will not release culpable individuals from civil or criminal liability when settling a matter with a corporation;

- DOJ attorneys should not settle matters with a corporation without a clear plan to resolve related individual cases; and,

- DOJ civil attorneys should focus on individuals as well as corporations and evaluate whether to bring suit against an individual based on considerations beyond an individual’s ability to pay.

The Yates Memo’s focus on holding individuals accountable may in the future be complemented by a proposal being discussed within DOJ regarding incentivizing voluntary disclosures of FCPA violations. In November 2015, The Washington Post reported that DOJ was discussing a draft policy whereby companies who voluntarily disclose FCPA violations and cooperate with DOJ would not be criminally charged or face a civil penalty. As part of a company’s disclosure and cooperation, DOJ would expect information about those individuals responsible for the FCPA violation. Critics of this draft policy contend that the practical effect of the proposal would be an increase in the number of declinations, even for cases where the reported misconduct is serious and substantial. To date, DOJ has not adopted this policy. Regardless, between the Yates Memo and this draft policy, DOJ has clearly revealed its intention to focus its resources on individuals in addition to corporations.

Cooperation and Voluntary Disclosures

Attorney General Lynch stated in her confirmation hearings that she disagreed with a proposed FCPA legislative “safe harbor provision” for corporations that self-disclose violations, cooperate with DOJ’s investigation, and have robust compliance programs. Ms. Lynch stated the she did not believe that a “safe harbor provision” is necessary or desirable and that DOJ already provides “significant benefits” to companies undertaking such actions.

Andrew Ceresney, Director of the Division of Enforcement at the SEC, reiterated that “companies are gambling if they fail to self-report FCPA misconduct.” He also echoed the policies set forth in DOJ’s Yates Memo and stated that it “has long been a central tenet of cooperation with the SEC” that to receive cooperation credit, the SEC expects to be provided with “all relevant facts, including facts implicating senior officials and other individuals.”

Increased Transparency

Assistant Attorney General Leslie Caldwell, head of DOJ’s Criminal Division, stated that one of her priorities is to “increase transparency regarding charging decisions in corporate prosecutions.” Ms. Caldwell also stated that she expects transparency from companies in return. “Transparency is a two-way street, and we expect companies that are claiming to cooperate to walk the walk.” Thus, while DOJ has “prioritized increased transparency in [] corporate investigations and prosecutions,” and will “strive to disclose more information,” it will “encourage companies to do the same—to self-disclose criminal violations and to cooperate with [ DOJ’s] investigations—or risk the consequences.” As an example of DOJ’s efforts on transparency, Ms. Caldwell highlighted that FCPA enforcement actions and opinion letters are posted to the Criminal Division’s FCPA website.

Along these same lines, in her confirmation hearings, Attorney General Lynch committed “to continuing the Department’s recent efforts to provide more information and transparency, as it did by publishing the [FCPA] Resource Guide.”

SEC Administrative Proceedings

In September, the SEC proposed changes to the way it conducts administrative proceedings. The main changes include the following:

- Adjusting the timing of administrative proceedings;

- Permitting parties to take depositions of witnesses as part of discovery; and,

- Requiring parties to submit filings electronically and to redact sensitive personal information.

The public comment period for these proposed changes concluded in early December 2015. These proposed changes come amid heightened criticism of the SEC’s use of administrative proceedings to resolve FCPA-related enforcement actions. For example, Rep. Scott Garrett (R-N.J.) introduced legislation H.R. 3798, the Due Process Restoration Act, which, according to Rep. Garrett, would “rein-in the [SEC’s] controversial overuse of in-house administrative law judges.”

III. What the DOJ/SEC is Doing

A. Corporate FCPA Enforcements

U.S. enforcement authorities continued to pursue FCPA violations by corporations aggressively, bringing major enforcement actions against 11 companies in 2015. Corporate penalty amounts totaled approximately $139 million.

The past year’s corporate FCPA enforcement actions are detailed in the chart below.

The year saw some familiar themes in FCPA enforcement. For example, two major SEC enforcement actions in 2015 – those against Mead Johnson Nutrition Co. and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. – demonstrate U.S. enforcement authorities’ continuing treatment of physicians in certain foreign health care systems as “foreign officials” under the FCPA, and the recent theme of FCPA actions premised on the actions of distributors.

- Mead Johnson: In July 2015, Illinois-based Mead Johnson agreed to pay more than $12 million to settle civil charges that it violated the FCPA with its China unit’s payment of $2 million in bribes to professionals at Chinese state-owned hospitals. Specifically, the SEC alleged that Mead Johnson violated the statute’s books and records provisions by failing to record properly the illegal payments and that the company lacked an adequate system of internal accounting controls. The SEC asserted that the “Enfamil”-maker’s employees used so-called “distributor allowances” to fund the bribes to Chinese health care professionals in exchange for their recommendation of Mead Johnson products to new and expectant mothers. The Mead Johnson enforcement action also underscores the risks inherent in the use of foreign distributors and other third parties. Notably, the SEC’s press release stated that, while “the funds contractually belonged to the distributors, [Mead Johnson] employees exercised some control over how the money was spent and provided specific guidance to distributors on how to use the funds.”

- Bristol-Myers Squibb: Mead Johnson’s parent company until 2009, Bristol-Myers Squibb, paid approximately $14.7 million to settle its own FCPA charges just a few months later, in October 2015. As with the Mead Johnson enforcement action, the SEC alleged that Bristol-Myers Squibb and its majority-owned joint venture in China violated the FCPA’s internal controls and recordkeeping provisions when joint venture sales representatives bribed health care providers at Chinese state-owned and -controlled hospitals (in the form of cash payments, gifts, meals, travel, entertainment, and conference sponsorships) to secure and increase sales. The SEC specifically noted that the company failed to respond properly to “red flags,” including discoveries at the joint venture of numerous irregularities in travel and entertainment expense reports and event documentation (such as fake and altered purchase orders) from 2009 through 2013.

Other settlements of note included:

- PBSJ Corporation: PBSJ, an engineering and construction firm, entered into a deferred prosecution agreement in which it agreed to pay $3.4 million and comply with a number of other undertakings to defer charges that it violated the anti-bribery and accounting provisions of the FCPA. The SEC alleged that a former PBSJ officer, Walid Hatoum, offered and authorized bribes disguised as “agency fees” to a company owned and controlled by a Qatari official to secure multi-million dollar development contracts in Qatar and Morocco. In exchange, the foreign official provided Hatoum and PBSJ’s international subsidiary (PBSJ Int’l) with confidential sealed-bid and pricing information. The foreign official then instructed PBSJ Int’l to lower its offer to a specific dollar amount, which enabled the company to tender bids that had a greater likelihood of being awarded. Notably, however, the allegations against PBSJ did not include payment of bribes—only the authorization of and promises to pay bribes. As such, the case serves as a reminder that an actual bribe is not necessary for FCPA liability to obtain—the offer or promise is enough.

- BHP Billiton: Mining company BHP Billiton agreed to pay $25 million to settle charges that it violated the books and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA by failing to oversee properly a “global hospitality program” related to its sponsorship of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. The SEC did not allege that BHP Billiton was ultimately successful in obtaining any particular business advantage through the program. Rather, the SEC chastised the company for being aware of the risk that the program could potentially violate anti-corruption laws and failing to implement sufficient internal controls to address that risk, highlighting that an internal controls violation can be independent of an anti-bribery violation.

- The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation (BNY Mellon): BNY Mellon agreed to pay $14.8 million to settle charges that it violated the anti-bribery and internal controls provisions of the FCPA by providing student internships to otherwise unqualified family members of government officials affiliated with a Middle Eastern sovereign wealth fund. The case represents a novel and somewhat controversial interpretation of what “anything of value” means under the statute, since the SEC did not allege that the foreign officials were provided with anything of monetary value. Instead, the SEC found that “[t]he internships were valuable work experience” and that “the requesting officials derived significant personal value in being able to confer this benefit on their family members.”

B. FCPA Actions Against Individuals

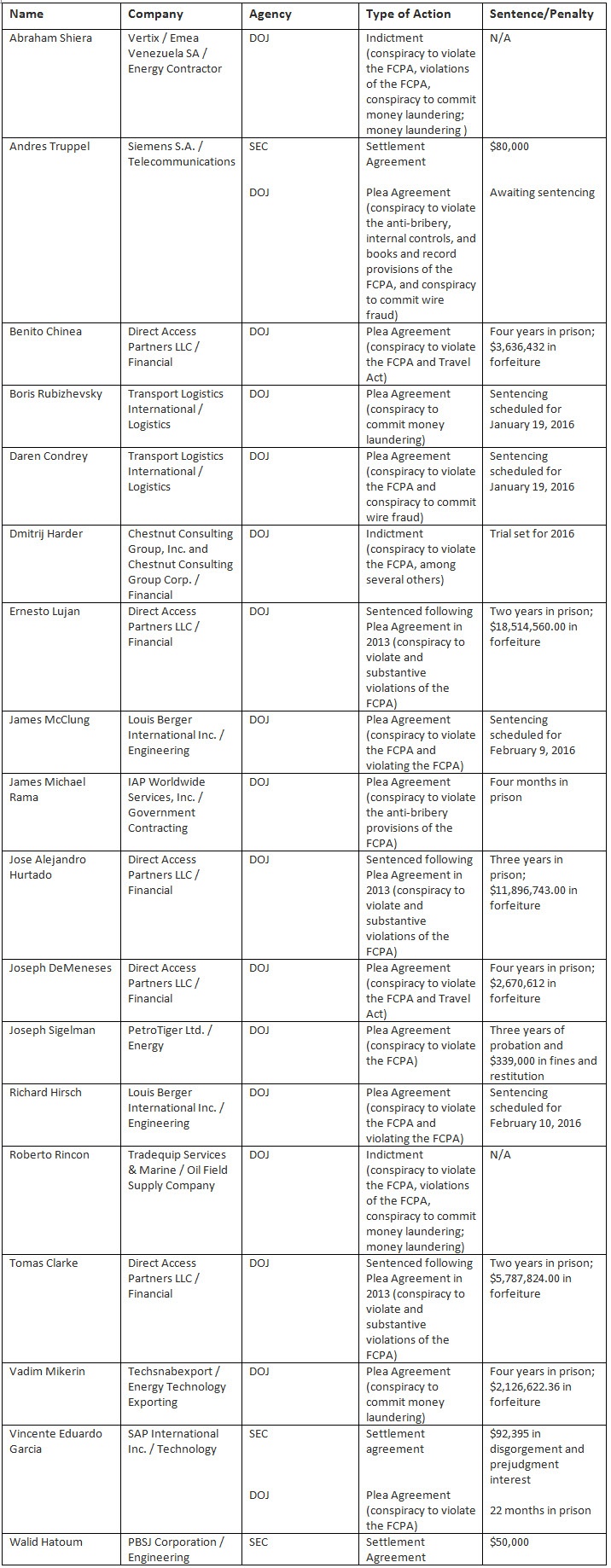

U.S. authorities continue to make good on their promise to focus on prosecuting individuals for FCPA violations. In 2015, U.S. authorities prosecuted and/or indicted 15 individuals on FCPA charges, and 11 of those individuals pleaded guilty to one or more charges. Notable prosecutions included that of Dmitrij Harder, which invoked the rarely used “public international organization” prong of the FCPA’s “foreign official” element, as well as the ongoing criminal case against Jean Rene Duperval, in which DOJ successfully used the Money Laundering Control Act (MLCA) as an anti-bribery enforcement tool to prosecute foreign officials who are not subject to the FCPA.

In United States v. Duperval, the agency successfully prosecuted Jean Rene Duperval, the director of international relations for Telecommunications at D’Haiti SAM (Haiti Teleco) who allegedly accepted approximately $500,000 in bribes paid in violation of the FCPA. At trial, DOJ established that the bribes paid to Duperval were proceeds of FCPA violations laundered through the U.S. financial system, a violation of the MLCA. In a separate case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit had previously found that Haiti Teleco qualified as an “instrumentality” of the Haitian government and that Duperval qualified as a “foreign official.” In 2015, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed Duperval’s subsequent conviction, thereby approving DOJ’s use of the MLCA as a complement to the FCPA in prosecuting corrupt foreign officials.

DOJ’s prosecution of a number of former high-level employees of the now-defunct brokerage firm, Direct Access Partners LLC (DAP), should be of particular interest to corporate executives. Former DAP executives Benito Chinea, Joseph DeMeneses, Jose Alejandro Hurtado, Tomas Clarke, and Ernesto Lujan were each charged with FCPA violations in connection with their paying at least $5 million in bribes to María de los Ángeles González de Hernandez, a vice president of a bank owned and controlled by the Venezuelan government. In exchange, Hernandez directed at least $60 million in business to DAP. Chinea, DeMeneses, Hurtado, Clarke, and Lujan pleaded guilty to the charges and were each sentenced in 2015 to terms of imprisonment ranging from two to four years. The former DAP executives were also ordered to forfeit more than $42.5 million in ill-gotten gains.

Additionally, DOJ indicted Roberto Rincon, the former president of Tradequip Services and Marine, an oil and gas services company. In this case, the alleged improper conduct relates to a scheme to secure energy contracts from Petroleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA). Specifically, DOJ alleged that Rincon and others’ conduct enticed PDVSA officials to list multiple companies owned or controlled by Tradequip as eligible to bid on certain contracts, thus creating an illusion of competition. It thus serves as an interesting illustration of the type of benefit that may satisfy the “obtaining or retaining business” prong of the anti-bribery provisions.

But the apparent success was not without significant setbacks. While corporate settlements are often the result of corporations’ reluctance to engage in prolonged and public FCPA battles, individuals may have a greater incentive to challenge the DOJ’s expansive interpretation of the FCPA. Two notable cases are highlighted below:

- United States v. Hoskins

- DOJ contended that Lawrence Hoskins, a British national and former senior vice president at a French energy firm, was subject to criminal FCPA liability for acts committed overseas under a theory of conspiracy or aiding and abetting.

- A judge rejected that argument as an unacceptable expansion of jurisdiction under the FCPA. Specifically, the judge held that a non-resident foreign national acting abroad could not be subject to criminal liability under the FCPA based on traditional theories of accomplice liability. Instead, DOJ must show that the defendant acted as an agent for a domestic concern. Absent a direct relationship between the defendant and the domestic concern, this may be difficult to prove.

- United States v. Sigelman

- PetroTiger Ltd.’s former CEO, Joseph Sigelman, was indicted on six counts relating to violations of the FCPA and faced up to 20 years in prison.

- The case ended mid-trial after a key government witness admitted to lying on the stand. Prosecutors then agreed to a plea agreement in which Sigelman pleaded guilty to only one charge (conspiracy to violate the FCPA). Despite DOJ’s recommendation, Sigelman received no jail time, but was instead sentenced to three years of probation and fined $339,000.

IV. The FCPA in 2016 and Beyond

The FCPA continues to be a significant enforcement priority for DOJ and SEC. The number of DOJ staff dedicated to fighting foreign corruption continued to grow in 2015, and the U.S. government’s rhetoric remains sharp. While these are hardly groundbreaking observations, the message is worth repeating for good reason: it’s true and many companies and individuals have not taken it sufficiently to heart.

FCPA enforcement may, however, look somewhat different in 2016. For one, it remains to be seen how DOJ’s re-calibrated cooperation approach will manifest in practice. While some remain concerned that the articulated approach will set an almost impossible cooperation standard, others foresee a new era of smaller penalties and more declinations for corporations that choose the open-kimono path in contrast to steep, “top ten caliber” penalties for those corporations selecting an alternative path. It also remains to be seen how DOJ’s new “compliance expert” will factor into the settlement process, but most expect that input from that new position will result in greater scrutiny of “enhanced compliance programs” proposed by companies in settlement discussions.

It also seems reasonable to expect additional focus on individual enforcement actions going forward. As in past years, the government has continued to emphasize the importance of pursuing FCPA violations by individuals. While, to date, DOJ has only enjoyed modest success in meeting this goal, its recent policy recalibration has the potential to move the needle. Should DOJ define “total cooperation” as requiring corporations to identify and turn evidence against “at fault” individuals, we could see the number of individual enforcement actions rise steeply.

Authors

Practice Areas

- Civil Fraud, False Claims, Qui Tam and Whistleblower Actions

- Congressional Investigations and Oversight

- Criminal Investigations and Prosecutions

- FCPA and Anti‑Corruption

- Government Contracts

- Internal Investigations and Compliance Programs

- International Trade

- White Collar Defense & Government Investigations