The Year of the Supplemental Protest

Several years ago, as debates over the bid protest process were heating up, we started to take a deeper, data-driven dive into the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) bid protest caseload. Although GAO’s annual reports are useful tools for tracking how GAO’s caseload has fluctuated over the years or how stable its “effectiveness rate” has remained, they do not provide, in and of themselves, much material for deeper analysis. To more fully analyze protest-related statistics, we started to collect data that GAO publishes daily on its docket. After collecting a full year’s worth of data in 2016, we shared several of our notable findings in A Data-Driven Look at the GAO Protest System. The finding that most grabbed our attention related to the power of a supplemental protest: Of all the cases that GAO decided on the merits in FY16 (in a decision either sustaining or denying the protest), protesters who identified no supplemental protest grounds succeeded in only 12% of the cases, while protesters who filed at least one supplemental protest succeeded in at least 22% of the cases.

We believe this connection is more correlation (protests more likely to succeed tend to be ones where new issues are discovered and pursued) than causation (simply filing a supplemental protest increases a protester’s success rate). For example, in many cases, agencies provide offerors with debriefings that give only the slightest peek into their evaluation process and findings. And even when agencies provide robust debriefings, they still cannot disclose their full evaluation record, especially as it relates to the other competitors. As a result, most initial protests rely on limited information about how the agency evaluated the offerors’ proposals (and how the agency erred). After all, the documents that most offerors rely on for their initial protests–the debriefing notes and slides–are irrelevant to GAO’s ultimate decision, which depends on the contemporaneous evaluation record. Thus, in preparing initial protests, companies do so in significant part so that they can obtain more information and then, with the advice of their outside counsel under the protective order, make a more informed decision about whether to continue to pursue the original protest grounds and any new supplemental protest grounds. By contrast, when protesters prepare supplemental protests, their counsel does so with the benefit of the contemporaneous evaluation record. Thus it is no surprise that protesters tend to be more successful when they raise challenges based on what they discover in the contemporaneous evaluation record (generally supplemental protests) than when they raise challenges to an evaluation record that they hope to gain access to during the protest process (initial protests).

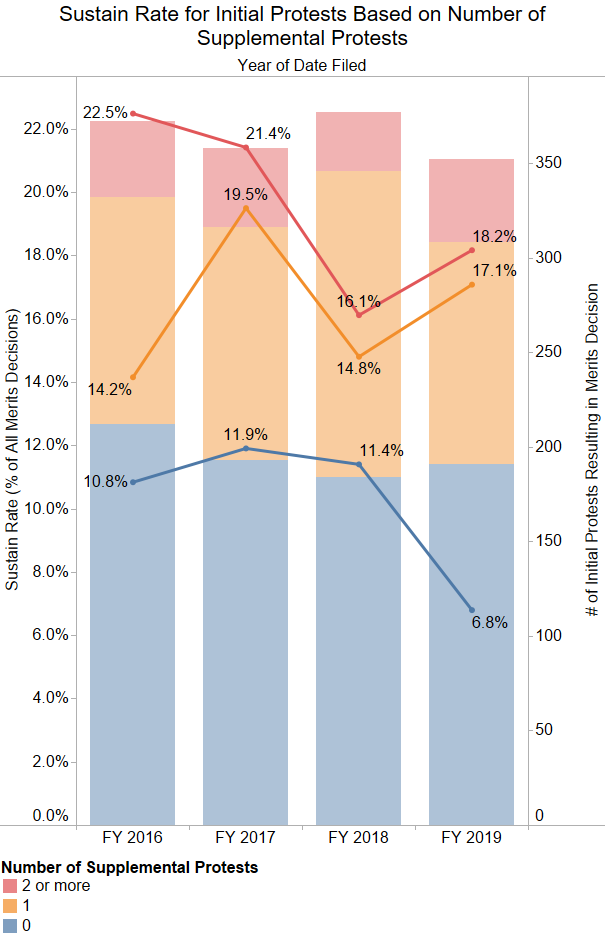

In the three years since we wrote our last article on this topic, the differences in odds have fluctuated, but they consistently remain in favor of the protesters who dig into the record and identify supplemental protest grounds. In fact, the data from the most recent fiscal year (FY19), shows this gap is bigger than it has been in any of the last four years. In its latest annual report, GAO reported its third straight drop in sustain rate, most recently from 15% (for cases closed in FY18) to 13% (for cases closed in FY19). But digging deeper–isolating standalone protests from supplemented protests–shows that protesters who filed supplemental protests in FY19 were more likely to succeed than they were in FY18. The drop in GAO’s reported sustain rate has thus been at the expense of those protesters who did not identify any supplemental protests. Looking at protests against all agencies as outlined in the figure below, protesters who filed one supplemental protest experienced at 17% sustain rate (orange line), while those who identified no supplemental protests, experienced a 7% sustain rate (blue line).

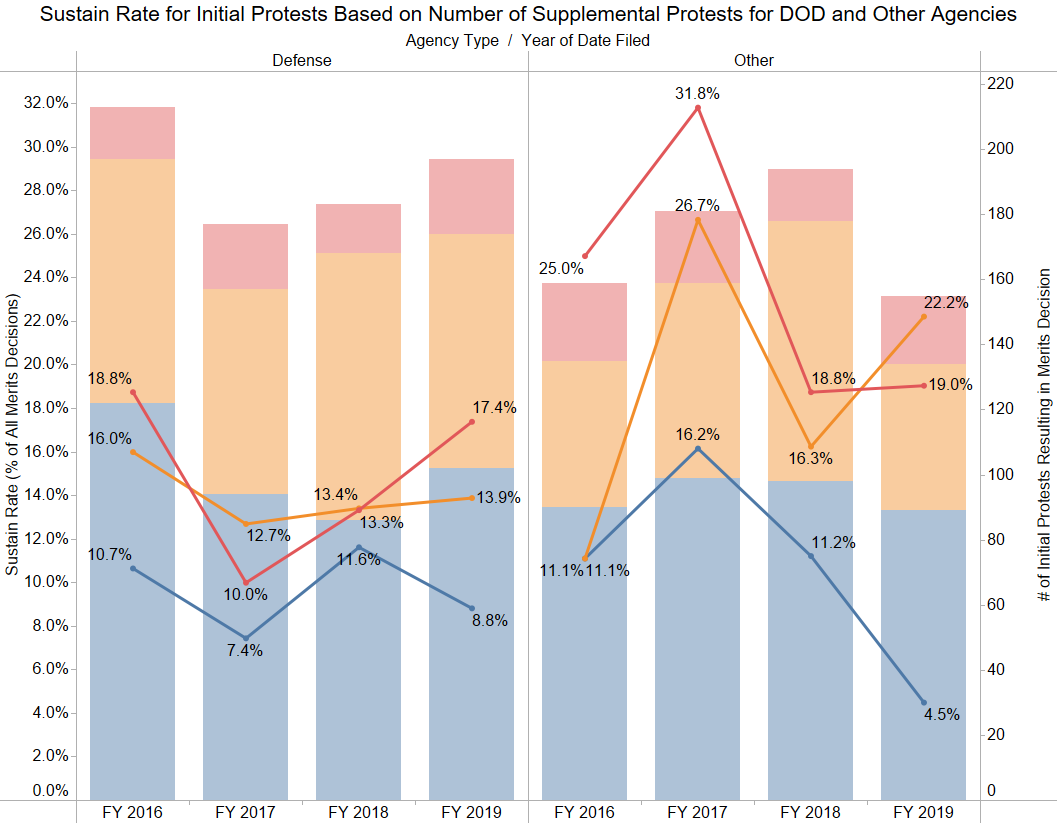

This rate, however, can vary by agency. For example, comparing all U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) agencies with all other agencies in FY19 shows that a supplemental protest against a DOD agency will not quite double the protester’s odds, while a supplemental protest against a non-DOD agency could multiply the protester’s odds by five times.

Of course, not all supplemental protests are equally effective, and probabilities can’t make up for a nuanced understanding of each individual case. The lesson here is not that protesters should submit more pleadings, but that they should understand that there is almost always more to learn after the initial protest is filed.