The Return of Sweet Home in the Texas Whooping Crane Case, and a Sign that ESA Is on its Way to SCOTUS

Recent Endangered Species Act (ESA) appellate court decisions provide greater protection from liability for “takings” of endangered species but also more uncertainty about the deference owed to federal agencies during consultation.

A Fifth Circuit Endangered Species Act (ESA) decision in June should increase the comfort of water users, growers, and pesticide registrants about “takings” claims. Aransas Project v. Shaw, 13-40317, 2014 WL 2932514 (5th Cir. June 30, 2014), provides the clearest statement to date that agencies that grant permits or licenses for water or pesticide use (and the private parties who receive them) are not responsible under the ESA for every subsequent harm to listed species. Such a clear boundary on the reach of the ESA should give government agencies a freer hand in issuing permits and licenses. In the Aransas Project case, a three-judge panel found that a Texas state agency's issuance of a permit allowing private parties to withdraw upstream water was not a foreseeable cause of the downstream deaths of 23 endangered whooping cranes. In short, the court found that the chain of causation from permit issuance to the death of the birds was too attenuated and too remote to support a “taking” claim against the permit issuer.

The Aransas ruling provides some protection to water users, state permitting entities, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) when defending alleged “takings” of threatened or endangered species. State agencies and EPA, for their part, take a wide range of licensing actions, from routine permitting to issuance of pesticide registrations, which potentially could result in the “take” of an endangered or threatened species. And, although the water users and farmers who benefited from the permits were not defendants in the Aransas case, the decision's reasoning should apply equally to them, as long as they are drawing water consistent with state-issued permits or applying pesticides in accordance with EPA-administered labels.

But this Fifth Circuit case is not the only ESA litigation to watch. Earlier this Spring, the Ninth Circuit created headlines (and a split among federal appellate courts) when it upheld in San Luis & Delta-Mendota Water Authority v. Jewell, 747 F.3d 581, 592-93 (9th Cir. 2014), petition for rehearing en banc denied, No. 11-15871 (9th Cir. July 23, 2014), a biological opinion (BiOp) of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS). That BiOp in essence denied 20 million agricultural and domestic users access to water from the Central Valley Project in California, in order to protect a small number of even smaller fish known as the delta smelt. And, in doing so, it granted considerable deference to the FWS's views.

Individually, these circuit decisions both promise immediate changes in the ESA context: one better protects government agencies and private parties from ESA civil and criminal penalties, and the other may lessen the duties of the consulting services when explaining the denial of a permit or license. And, taken together, ESA litigation likely will result in a meaningful Supreme Court opinion in the not-too-distant future, with far-reaching implications for water users, landowners, and pesticide users.

Background of Aransas Litigation

The central importance of Aransas is its conclusion that environmental challengers must show that permitting action is a foreseeable cause of the “take” of a threatened or endangered species. But the road to Aransas began with an earlier Supreme Court decision that in large part introduced the requirement that plaintiffs must prove proximate cause in ESA Section 9 “takings” cases.

Under Section 9 of the ESA, a “take” means “to harass, harm . . . wound, [or] kill” protected species. 16 U.S.C. § 1532(19). A subsequent regulation implementing the provisions of the ESA clarified that “harm” includes—beyond direct harm to a protected species—“significant habitat modification or degradation where it actually kills or injures wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding or sheltering.” 50 C.F.R. § 17.3(c).

This regulation could be interpreted expansively: to make state and federal agencies liable for a “take” whenever harm resulted to a protected species, its behavioral patterns, or its habitat, with a continuing threat of liability during the entire term of a license or permit. Such a broad interpretation would constrict agencies' ability to issue water permits and pesticide registrations. But the Supreme Court chose a narrower interpretation in Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter, 515 U.S. 687, 700 n. 13 (1995). As a result, an agency is only liable where its action was the proximate cause of the taking of a listed species, and not for every subsequent harm that may occur after the initial grant of a license or permit. The explication of this requirement was provided in a concurrence by Justice O'Connor: if “a farmer who tills his field and causes erosion that makes silt run into a nearby river which depletes oxygen in the water and thereby injures” a protected species, the farmer likely would not face “take” liability. Id. at 713 (O'Connor, J., concurring). Instead, ESA “take” liability extends only to “foreseeable rather than merely accidental” actions. Id. at 709 (O'Connor, J., concurring). This limitation, according to Justice O'Connor, “depends to a great extent on considerations of the fairness of imposing liability for remote consequences” and on the particular facts of a case. See id. at 713 (O'Connor, J., concurring) (stating that “[t]he task of determining whether proximate causation exists in the limitless fact patterns sure to arise is best left to lower courts”).

The Aransas Decision

At bottom, the application of proximate cause places a limitation on liability for the “take” of a listed species, so that state and federal agencies (and the users who receive permits or licenses from these agencies) are not liable for harm that is far removed from the issuance of the permit. But because it is a fact-dependent standard, guidance from subsequent cases is particularly important. Aransas is the most recent of these subsequent cases to better insulate government agencies and private parties from the risk of litigation for “takings” under the ESA. The Court of Appeals' Aransas decision found that a federal district court in Texas had ignored the proximate cause requirement when it imposed liability on a Texas state agency for a too-remote harm to a listed species. The problem, according to the court, was the District Court's “untethered linking of governmental licensing” with every resultant harm to an endangered species. The appellate court held that “[f]inding proximate cause and imposing liability . . . in the face of multiple, natural, independent, unpredictable and interrelated forces affecting the cranes' [habitat] goes too far . . . . ” Aransas, 2014 WL at *14.

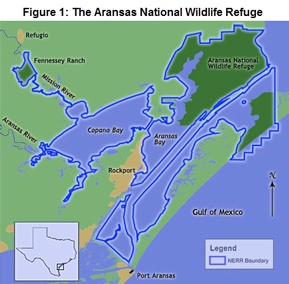

The species at issue was the whooping crane, which is listed as endangered under the ESA. According to the court record, the world's only wild flock resides in Aransas National Wildlife Refuge (depicted in Figure 1) during each winter before migrating to Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada in the summer. Id. at *1. Between 2008 and 2009, an estimated 23 of these 300 wild cranes in the flock died. The Aransas Project (TAP) sued directors of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) under the ESA for committing an unauthorized “take” of the cranes.

Source: Lee Clippard, Univ. Tex.-Austin, Living Laboratory

http://www.utexas.edu/features/2006/estuarine/.

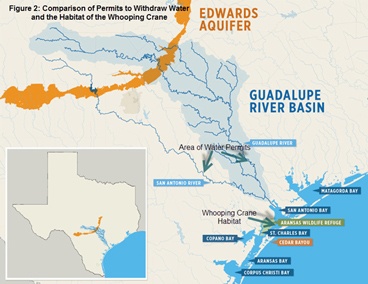

The TCEQ regulates surface-water use in Texas through the issuance of permits. Id. In this case, TCEQ had issued permits to private parties to withdraw surface water from the San Antonio and Guadalupe Rivers. TAP argued that the TCEQ committed an unauthorized take of the 23 cranes by issuing these permits to private water users for withdrawing water from the rivers,

in turn leading to a significant reduction in freshwater inflow into the San Antonio Bay ecosystem. That reduction in fresh-water inflow, coupled with a drought, led to increased salinity in the bay, which decreased the availability of drinkable water and caused a reduction in the abundance of blue crabs and wolfberries, two of the cranes' staple foods. According to TAP, that caused the cranes to become emaciated and to engage in stress behavior, such as denying food to juveniles and flying farther afield in search of food, leading to further emaciation and increased predation. Ultimately, this chain of events led to the deaths of twenty-three cranes during the winter of 2008–2009.

Id. at *2. The district court accepted TAP's theory of causation (illustrated graphically in Figure 2) and held that the TCEQ had violated the ESA through their water-management practices. Id. at *3.

Source: The Aransas Project, A Troubled Basin

http://thearansasproject.org/situation/basin-management/.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit reversed. Relying on the Supreme Court's 1995 Sweet Home ruling, the Fifth Circuit held that “proximate cause and foreseeability are required to affix liability for ESA violations.” Id. at *12. The court determined that the long chain of causation separating TCEQ's issuance of a permit from the death of any individual crane, of which every link required “modeling and estimation,” made the TCEQ's actions too remote, attenuated, and unforeseeable to be considered the proximate cause of the cranes' deaths. Id. at *15. As a result, the court determined that as a matter of law, proximate cause and foreseeability were lacking. Id. at *17.

Aransas in Light of Decisions of Other Federal Circuit Courts

Appellate courts in other circuits generally agree with the Aransas decision that actions that are too attenuated (and thus not foreseeable) do not constitute a take under the ESA. But the unique contribution of Aransas, unlike prior cases from other circuits, is that it resulted in a conclusion that the agency was not liable. As a result, the Aransas decision gives the clearest statement yet of the outer limits of causation under the Sweet Home proximate cause doctrine.

Earlier cases from other circuits went the other way, finding actions sufficient to meet the proximate cause standard. For instance, in Strahan v. Coxe, 127 F.3d 155, 158 (1st Cir. 1997), Massachusetts officials were found to have violated the ESA for issuing licenses that authorized gillnet and lobster pot fishing. The officials knew that “entanglement with commercial fishing gear . . . is a major source of human-caused injury or death to the Northern Right whale” and numerous whales were previously found with such injuries. Though Massachusetts argued that the mere licensing action could not satisfy proximate cause, the First Circuit disagreed. Rather, granting licenses to use gillnets and lobster pots foreseeably, and perhaps even expectedly, causes injury to endangered whales. A similar case is Animal Prot. Inst., Ctr. for Biological Diversity v. Holsten, 541 F. Supp. 2d 1073, 1077–78 (D. Minn. 2008), in which the District Court found that the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources had, by authorizing and allowing third parties to engage in trapping and snaring activities, taken the endangered Canada Lynx.

One way to conceptualize this standard is to assess whether a gap (which may include a gap in time, space, or an event outside the control of the authorizing agency or the holder of a permit) exists between the action authorized by a permit or license and the harm to the endangered species. In both Coxe and Holsten, trappers or fishers receiving licenses harmed the endangered species as part and parcel of that license or permit. No intervening gaps existed between their actions (trapping and fishing) and the harm to endangered species (injury caused by snares and nets).

In fact, in cases where a government licensing agency or person who received such a license was found to have proximately caused a “take,” the action authorized by a license or permit directly resulted or foreseeably could result in harm to the endangered species. See Loggerhead Turtle v. Cnty. Council of Volusia Cnty., Fla., 148 F.3d 1231, 1258 (11th Cir. 1998) (failure to regulate beach front artificial lightning caused endangered turtles to crawl in the direction of the light and to get run over by traffic); Sierra Club v. Yeutter, 926 F.2d 429, 438–39 (5th Cir.1991) (timber company logging practices would result in illegal take of endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers); Defenders of Wildlife v. EPA, 882 F.2d 1294, 1301 (8th Cir.1989) (registration of pesticides containing the harmful chemical would result in illegal “take” when pesticides sprayed on crops); Animal Welfare Inst. v. Martin, 588 F. Supp. 2d 70, 99 (D. Me. 2008) (Maine's issuance of trapping licenses likely to lead to prohibited takings); Seattle Audubon v. Sutherland, CV06-1608MJP, 2007 WL 1300964 (W.D. Wash. May 1, 2007) (logging in an area occupied by an endangered owl could result in harm); Pacific Rivers Council v. Oregon Forest Indus. Council, No. 02-243-BR, 2002 WL 32356431 at *11 (D.Or. Dec. 23, 2002) (state forester's authorization of logging operations likely to result in a take sufficient for liability).

But Aransas follows a different pattern. The death of the cranes was not caused by the water users who received a government permit to withdraw water. Rather, several intervening events existed between the action authorized by the permit and the harm to the cranes. The plaintiffs argued that the deaths of the cranes were caused by a chain of events: the withdrawal of water increased the salinity of the water, which then flowed from the river into a bay and estuary, which in turn reduced the cranes' food source, which then led to stress migration, and which finally led to emaciation and death of the cranes. The new contribution from Aransas is thus to define of the outer limits of proximate cause, at which point the authorizing agency is no longer liable for any harm. Aransas, in combination with the cases from the other circuits, shows that any intervening steps in the chain of causation that separate the action authorized by a permit to withdraw water or apply pesticides and the harm to species cast into doubt whether the government agency can be considered the proximate cause of the “take” of an endangered species.

Not every circuit has followed the proximate cause analysis first employed in Sweet Home and most recently applied in Aransas. In the Ninth Circuit (encompassing Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) and Eleventh Circuit (Alabama, Florida, and Georgia), for example, proximate cause as defined in Aransas and Sweet Home may not be the standard for government licensing and permitting activities. SeeLoggerhead Turtle v. County Council of Volusia County, Fla., 148 F.3d 1231, 1251 n.23 (11th Cir. 1998); Palila v. Hawaii Dep't of Land & Natural Res., 852 F.2d 1106, 1107 (9th Cir. 1988).1 In Loggerhead, the Eleventh Circuit expressed some reluctance to adopt the proximate cause requirement in Sweet Home, and found that a county could be held liable for not regulating beachfront lighting, which in turn caused endangered turtles to crawl toward the lighting, where they were subsequently injured by vehicles. Loggerhead Turtle, 148 F.3d at 1251 n.23.

But these cases are both more than 15 years old (and the Palila case predates Sweet Home and was disclaimed by Justice O'Connor's Sweet Home concurrence), so Aransas may be persuasive even in these outlying regions. Indeed, one federal district court in California, in the Ninth Circuit, recently found the approach in Aransas persuasive. See California River Watch v. Cnty. of Sonoma, C 14-00217 WHA, 2014 WL 3377855 (N.D. Cal. July 10, 2014) (relying on Aransas to find that “the plaintiff did not meet its burden of proving” causation because its claim that land development would endanger protected salamander populations required the use of approximation and modeling).

Other Developments in ESA Litigation

The Fifth Circuit is not the only forum for retesting the limits of the ESA. Since the enactment of the ESA, courts have balanced the protections afforded to endangered species against the need for state and federal agencies to fulfill their statutory responsibilities to register pesticides, apportion water, and provide power. Great deference has been given to the Supreme Court's 1978 ruling that “[t]he plain intent of Congress in enacting this statute was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost.” Tenn. Valley Auth. v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153, 184 (1978). In TVA v. Hill, this broad protection led the Supreme Court to halt construction of a $100 million dam to ensure the “survival of a relatively small number of three-inch fish.” Id. at 172-73. Even in Sweet Home, other members of the majority were not prepared to join in Justice O'Connor's concurrence.

But a case testing the deference owed to action agencies and the consulting services under Section 7 may soon present an opportunity for the Supreme Court to revisit this balance. In its March San Luis decision, the Ninth Circuit reinstated a 2008 FWS BiOp that urged restriction of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's delivery of water from the Sacramento Delta to over 20 million agricultural and domestic water users in central and southern California. The concern at issue was potential effects on the delta smelt, a two to three inch fish in danger of extinction, from diverting water from the Sacramento River. San Luis, 747 F.3d at 592-93. Despite recognizing the legitimacy of concerns with several aspects of the modeling and analysis on which the BiOp's “reasonable and prudent alternatives” (RPAs) were based, the court held it was obliged to defer to the expertise of the Service, whatever the economic implications.

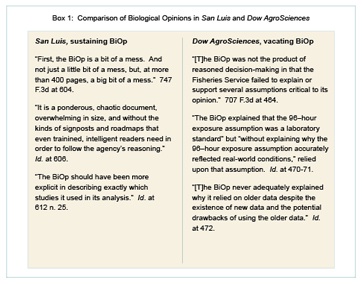

The San Luis decision expressly rejected the opposite conclusion that had been reached by the Fourth Circuit last year in Dow AgroSciences LLC v. National Marine Fisheries Service, 707 F.3d 462 (4th Cir. 2013). There, the court vacated a National Marine Fisheries Service BiOp that addressed the potential impact of use of several pesticides on salmon. The difference in results, despite similar criticisms of the BiOps, between the two courts' views is demonstrated in Box 1.

Box 1: Comparison of Biological Opinions in San Luis and Dow AgroSciences

The difference between the San Luis and Dow AgroSciences holdings is not academic. The delta smelt decision has far more immediate impact than Dow AgroSciences. In light of the ongoing California drought San Luis means that much of the enormously-fertile San Joaquin Valley and areas south will be denied the water. And the decision creates a circuit split that could result in Supreme Court attention.

Technically, that split arises from the two courts' different handling of several issues. The first is how the consulting services must consider the economic feasibility of reasonable and prudent alternatives to a planned action. Cf. 50 C.F.R. § 402.02. Whereas San Luis held that BiOp is not required to address the economic feasibility of alternatives, Dow AgroSciences favored a robust economic analysis of alternatives, based on the regulations implementing the ESA. Second, the two cases also differ in their approach to assessing the feasibility of alternatives on third parties. Whereas San Luis held that the impact on third parties need not be addressed in a BiOp, Dow AgroSciences suggested that consequences of a particular action on third parties must be addressed.

Resolution of either of these issues could have far-reaching implications. And, if the case reaches the Supreme Court, it could lead the Supreme Court to revisit two conclusions of the seminal 1978 Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill decision that have provided the underpinnings of a great deal of ESA precedent ever since. These contrasting decisions by panels in two separate appeals courts regarding ESA consultations provide a basis to elevate San Luis to the Supreme Court.

Summary and Immediate Impacts

These recent appellate court decisions show that the ESA is a still-active area of environmental litigation, rife with new developments and potential for Supreme Court development. With debates about the scope of proximate cause in ESA take cases, and how much deference is owed to environmental authorities, that have created circuit splits, it is foreseeable, and perhaps even likely that one or more of these issues is on the path to being granted a writ of certiorari by the Supreme Court.

Until the Supreme Court acts, however, Aransas promises the most immediate nationwide impact. It affects the day-to-day operations of pesticide registrants, farmers, or water users across the nation operating on government licenses or permits who may be concerned about the threat of continuing liability for harm that may be far separated in time or distance from the original issuance of a permit or license. Aransas places an outer limit on such liability, providing additional protection to private parties and the government agencies that issue licenses and permits.

But the impact of the San Luis case also is real, as California struggles with a historic drought that may or may not be ameliorated by new legislation promoted by California Senate and House delegations. Moreover, if San Luis reaches the Supreme Court, the case could change the landscape for how much deference should be given to a federal agency's analysis and conclusions in an ESA action and what role economic and technical feasibility should play in such decisions. Any future ruling that changes the extent to which agencies must consider economic implications in their ESA-related actions could have extraordinary implications.

__________________________________

1 One District Court has reached a similar result. See Animal Prot. Inst., Ctr. for Biological Diversity v. Holsten, 541 F. Supp. 2d 1073, 1078 (D. Minn. 2008) (“First, the Court notes that the footnote in the Sweet Home decision relied upon by Defendants is dicta”) (citing Loggerhead, 148 F.3d at 1251 n.23).

__________________________________

2014 Summer Associate Andy Wang contributed to this article.